Most people already know the basic checks before opening a file. They also apply to PDFs: verifying the sender looks legitimate, exercising caution before opening or downloading unexpected attachments, and avoiding PDFs with double extensions (.pdf.exe, for instance). These are great habits that make it harder for you to fall prey to low-effort phishing attempts.

However, PDF attacks are evolving and don’t always follow the obvious route. These documents are structured containers capable of carrying hidden objects, digital signatures, and encryption metadata; they can execute actions. Treating them like passive documents means trusting them without even understanding them. This can be dangerous. Even though modern PDF readers may protect against some risks, they are not infallible. You should perform deeper checks to determine risks before opening any PDF.

Check the PDF’s execution capability before opening it

Active objects, automatic actions, and embedded payloads

PDFs are object-based formats built by linking objects like dictionaries, streams, arrays, and references. These documents are capable of supporting scripting and embedded files. They can be launch points for certain actions and can automatically trigger actions. The real risk with PDFs goes beyond the scope of what the document carries; it is what it can do.

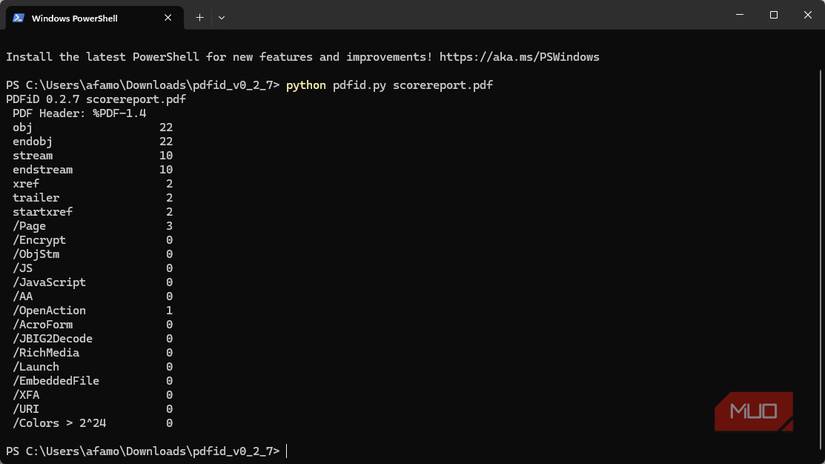

Whenever you receive a PDF, first determine whether it contains executable elements. And your best bet is running the command below after installing Python and the PDFiD Python-based command-line tool:

python pdfid.py C:\Users\You\Downloads\suspicious.pdf

From the results of the scan, if any of the following objects have a non-zero value, there may be some risk:

- /JS or /JavaScript

- /OpenAction

- /Launch

- /AA (additional actions)

- /EmbeddedFile

The table below shows what the objects may indicate:

Object | Why it matters |

|---|---|

/JS or /JavaScript | Used in obfuscation and exploit staging |

/OpenAction | Can trigger code automatically when the document opens |

/Launch | Can execute external applications |

/EmbeddedFile | Can contain secondary payloads |

/AA (additional actions) | Very similar to OpenAction |

Most legitimate files do not need these objects. For instance, /Launch is useless for an invoice. You don’t expect any static report to require embedded files. Having a high count for any of the objects mentioned does not automatically mean it is malware. However, they turn the PDF file from a document into an interactive container. You should use the pdf-parser.py tool for further inspection if the results return non-zero values for any of the mentioned key objects.

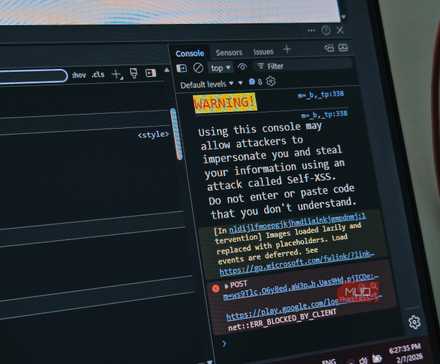

However, the rule of thumb for safety is to open the PDF in a sandbox or virtual machine if you’re in doubt. Also, scripting is not always evident, and its absence does not imply that malformed objects cannot exploit vulnerabilities in PDF readers. There have been several instances where CVEs came from parser weaknesses without visible scripting. JavaScript is only one element in execution capability; another significant element is how complex and likely to be triggered a structure is. You shouldn’t casually open any file that can execute, fetch, or save payloads.

Verify the document’s cryptographic integrity before trusting it

Digital signatures, certificate chains, and post-signing modifications

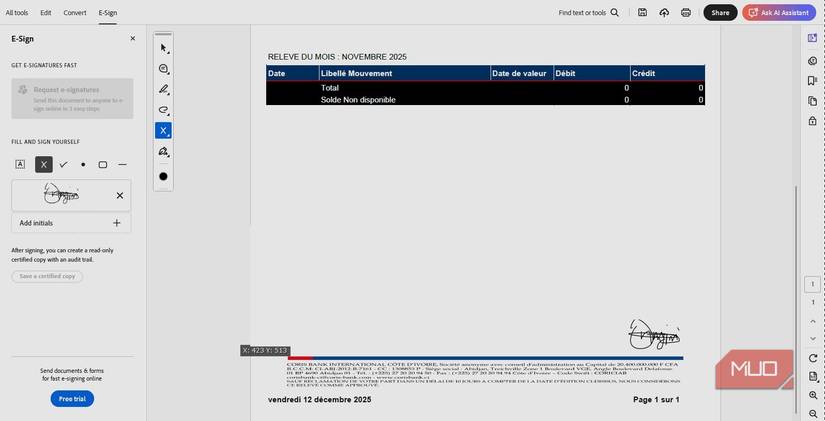

The mere presence of a logo or visible signature on a PDF doesn’t guarantee integrity. Integrity is validated only when there is a digital signature. Cryptographic signatures are built on public key infrastructure (PKI), and they can ascertain three things in PDFs: that the file hasn’t been changed (integrity), who signed it (authenticity), and its origin (non-repudiation).

If any PDF claims authority, you can run the same PDFiD scan explored earlier and look for the /AcroForm value. Any value above zero points to the presence of a signature form field. You can then open the file in isolation in Adobe Reader or any other advanced PDF tool and check the Signature Panel for the following:

- Is the signature valid?

- Does it chain to a trusted root certificate authority?

- Is the certificate expired or revoked?

- Was the document modified after signing?

- Is there a trusted timestamp?

This check is essential because it’s possible for a document to show a signature without having a cryptographic signature. Also, because a revision can be appended to a PDF after it has been signed, you must take special note of incremental updates. If the reader points to modifications post-signing, you should be cautious. The table below gives an integrity model for signatures.

Signature state | Meaning |

|---|---|

Valid and trusted | Integrity intact, signer verified |

Valid but self-signed | Integrity intact, identity unverified |

Broken or modified | Integrity compromised |

No signature | No cryptographic guarantees |

There are countless legitimate PDFs that remain unsigned, and this is normal. But the moment the file claims authority, which is the case with bank notices, legal forms, and enterprise contracts, it becomes a concern if it lacks a signature. Files that claim trust must be able to mathematically prove it.

Confirm the file’s provenance and structural consistency before interacting with it

Metadata alignment, delivery chain validation, and structural anomalies

Unsigned PDFs of unverifiable origin can be risky even when non-executable. To stay safe, you need to inspect the file’s delivery path. Three values must check out: SPF (Sender Policy Framework), DKIM (DomainKeys Identified Mail), and DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance). These email authentication protocols verify whether an email actually came from the domain it claims to be from. To check these paths, follow these steps:

- Open the email with the PDF attachment.

- Click the three dots at the top right of the email and click See original.

- Inspect the values for SPF, DKIM, and DMARC; if the values are PASS, the source checks out.

You can also quickly look through the email details to compare the display name to the actual sending domain. But more importantly, if the file was downloaded via a link, examine redirect chains. For this examination, copy the link and paste it into a tool like URL Scan to see every hop the file went through, including the original link. You may know if the link is clean by running it through VirusTotal’s URL checker. Next, inspect the actual file. You can install ExifTool and run the command below to find file values like Author, Creator, Producer, Creation date, and Modification date.

exiftool suspicious.pdf

Once you have these values, compare them to the PDF’s claims. If, for instance, a PDF is supposed to be a 2026 invoice from your multinational bank, but the producer’s information points to an outdated consumer LibreOffice build, it’s proof that something may be wrong. Lastly, run this qpdf command for structural consistency.

qpdf --check suspicious.pdf

Multiple incremental dates, excessive object streams, odd compression layers, and anomalies in cross-references may be signs that something harmful lies within.

Treat PDFs as executable containers, not passive documents

Even though a PDF may look like an ordinary sheet of paper when printed, the actual file is closer to a packed container. It can be an effective conduit for executing actions. To be safe, you must examine the mechanics underneath the file.

Using security apps is one way to stay safe online. However, a little pause and inspection before you open a PDF is a habit that will protect you when apps fail.

Your browser extensions can see every password you type

Your trusted extension/add-on with over 100k review might be spying on you.